HOW WE GET THERE

WHAT CHANGES CAN BE MADE TO MAKE ALABAMA COMPETITIVE?

Fortunately, there are many resources and examples Alabama can use to increase competition in pavement letting, and benefit from the reduced costs, congestion and frequent resurfacing that a two pavement program can bring.

Creating Competition

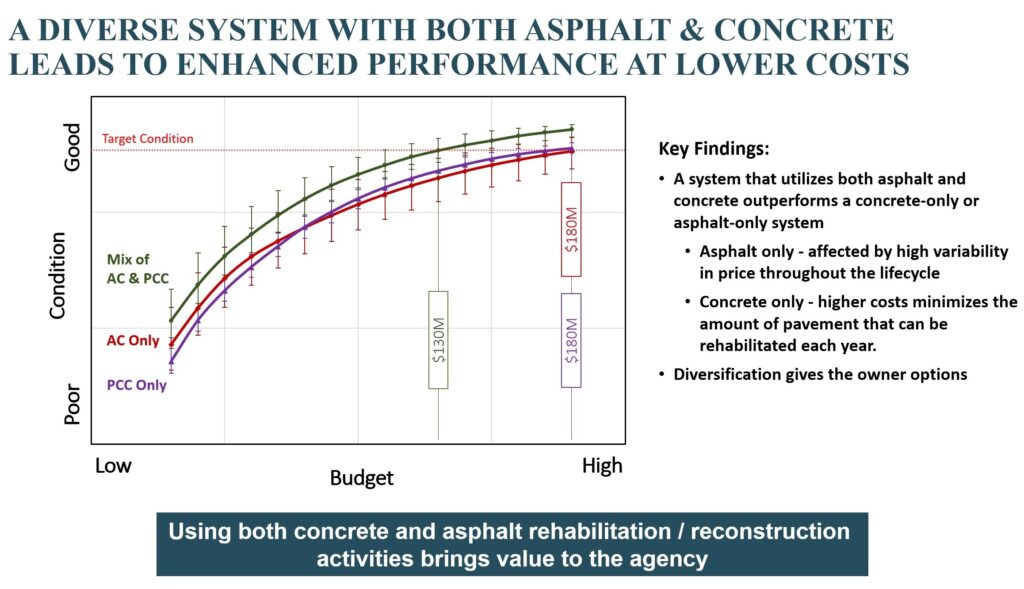

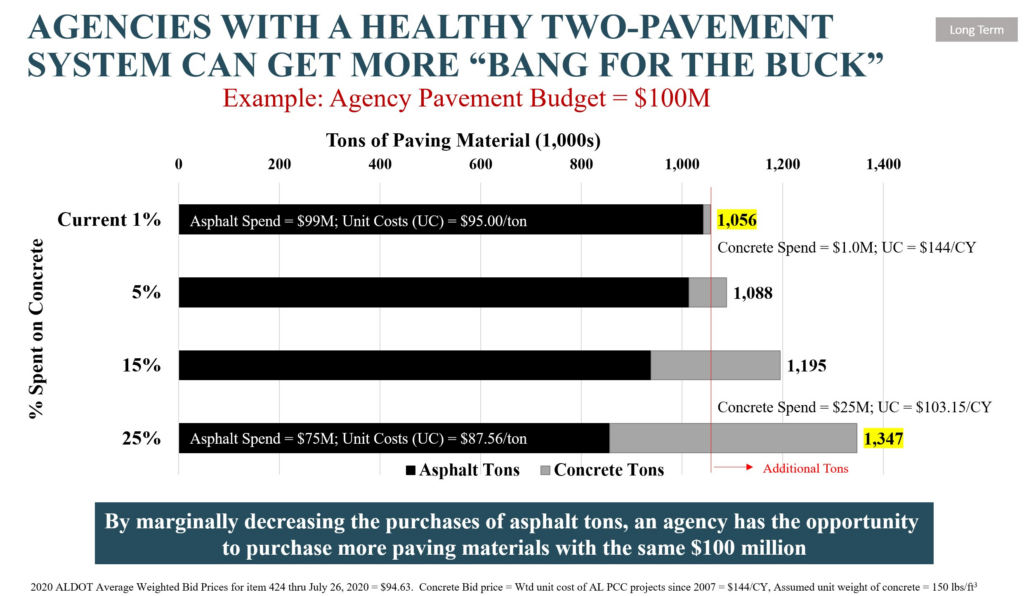

Often times, a DOT says that they do not have enough money to do concrete because they feel it is too expensive. This is not true. Transportation agencies have money; but they may be reluctant to allocate money to concrete because they think they will not be able to do as much work. However as shown above, this is a false choice.

Purposely investing in both concrete and asphalt paving will significantly lower costs for both paving materials and thus enable the DOT to do more. As such, this is not an argument of having or not having enough money, it’s about how the money should be allocated and it needs to be allocated to increase competition. The following steps can be used to clearly signal that the agency is serious about creating competition between the asphalt and concrete paving industries so that they, and the stakeholders within DOT take the necessary steps and make the necessary investments to create a competitive paving program.

The following steps can be used to clearly signal that the agency is serious about creating competition between the asphalt and concrete paving industries so that they, and the stakeholders within DOT take the necessary steps and make the necessary investments to create a competitive paving program.

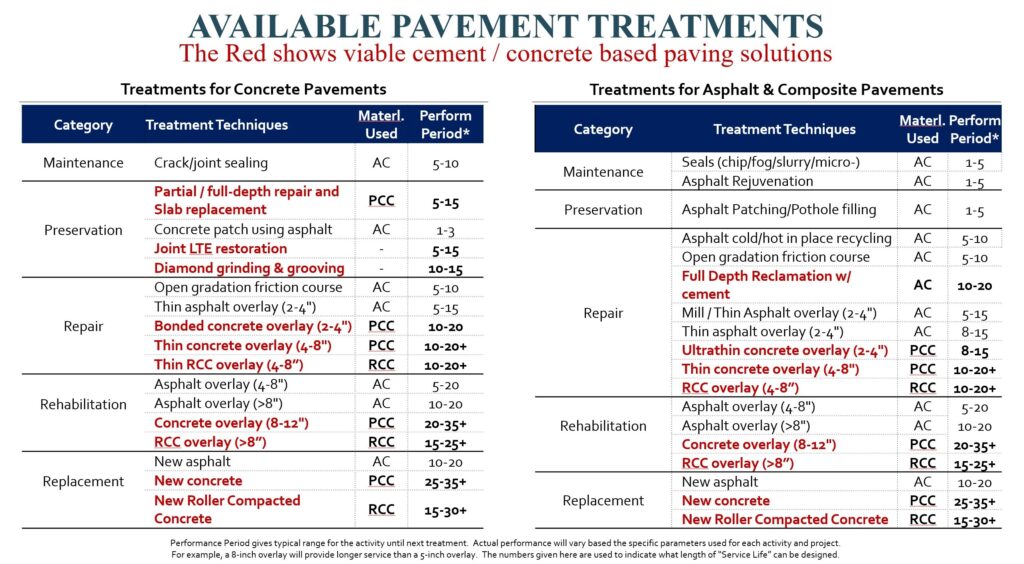

ALDOT Announces their Intention to Have a Concrete Paving Program & Adopts All Cement Based/Concrete Solutions

This signals to the market that there will be concrete and encourages contractors’ need to adapt

Announcing the DOTs intention to have a concrete paving program signals to both the concrete and asphalt paving industries that the DOT is serious about spurring competition and getting the benefits that long-term industry competition can bring.

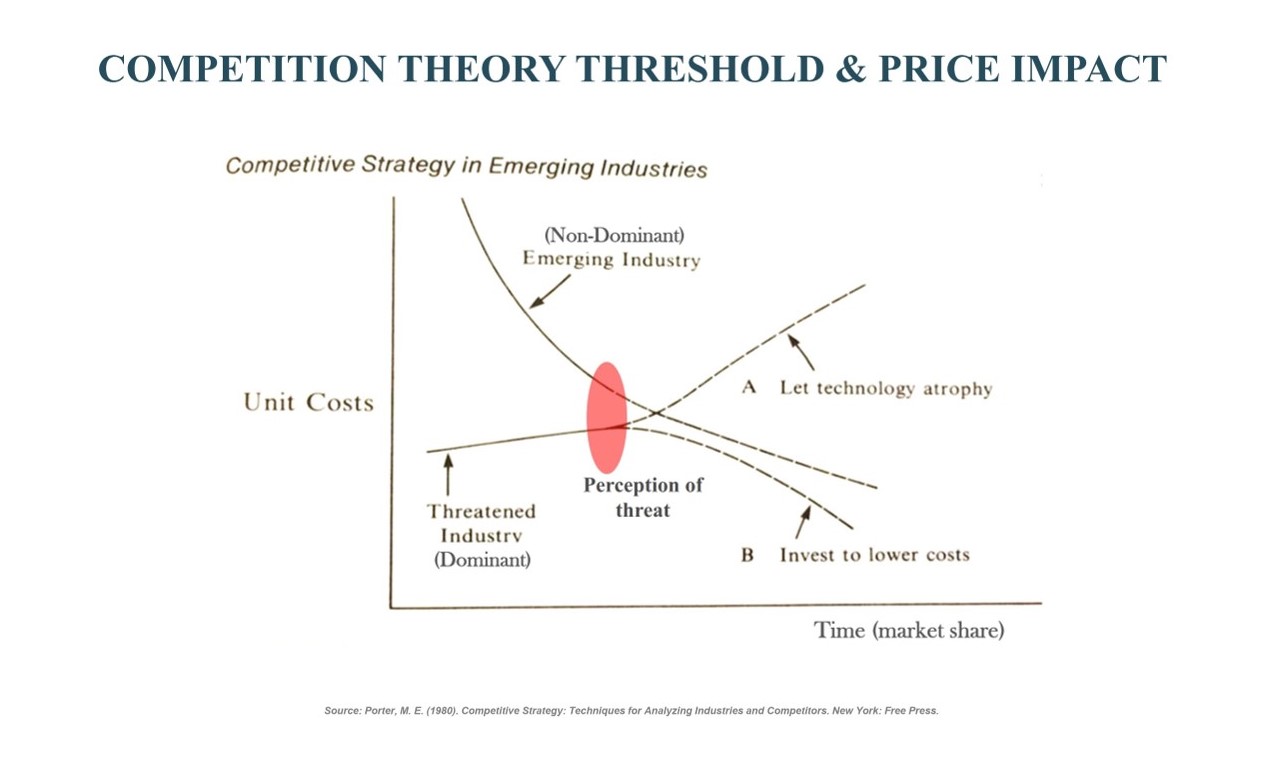

This signal helps create a “perception of threat” and incentivize both industries to innovate and develop the spirited competition that will lead to lower paving material costs.

Without the perception of a threat, the dominant industry is unlikely to compete on price and lower its unit cost until it sees the (re)emerging industry capture some portion of the market. Similarly, if the (re)emerging industry does not foresee that it will be able to capture a portion of the market, it is unlikely to invest to become cost-competitive.

ALDOT Purposely Lets a Given Number of Concrete Projects Each Year and Develops a Project Pipeline that Covers Several years

Processes to do this include:

Use Traffic/road classifications to designate specific markets for each product

The Minnesota DOT historically had an ESAL (Equivalent Single Axle Load) Rule. If a road had <1M ESALs, it was asphalt, >7M ESALs it was concrete, and roads with ESALs between 1 & 7M went thru an LCCA process.

Designate a given percentage of projects will be Concrete

This is the process followed by the Florida DOT and they do at least 10% (approximately 40 miles) of concrete pavement per year.

Programmatically balance the market based on some metric such as volumes

The Wisconsin DOT balances their program each year so that Tons of asphalt and square yards of concrete pavement are about the same volume year over year.

Just as agencies let projects that are only asphalt, DOT’s must also let some projects that are only concrete. Not only does letting concrete projects shows the local asphalt, earthwork, bridge and other contractors that they need to invest in new equipment and training for the new business opportunities, it also gives the DOT’s a better idea of what the true costs of concrete pavements are. Without consistent projects being bid, engineers cannot make reasonable cost estimates for concrete pavements.

When announcing their project pipeline, it is important that the DOT not only announces the first set or year’s projects, but they continually (every year) announce projects for several years out (e.g. 3 to 5 years in advance). Declaring a Multi-year pipeline does 3 things:

- First it ensures that concrete projects will be brought forward during the development stage;

- Secondly, it indicates to the contractors that there is a pipeline of projects and they need to continue buy equipment, train their workers, and be prepared for the concrete pavement program;

- Finally, by publishing the plan lets contractors see what projects will be coming up for bidding so they can plan more effectively.

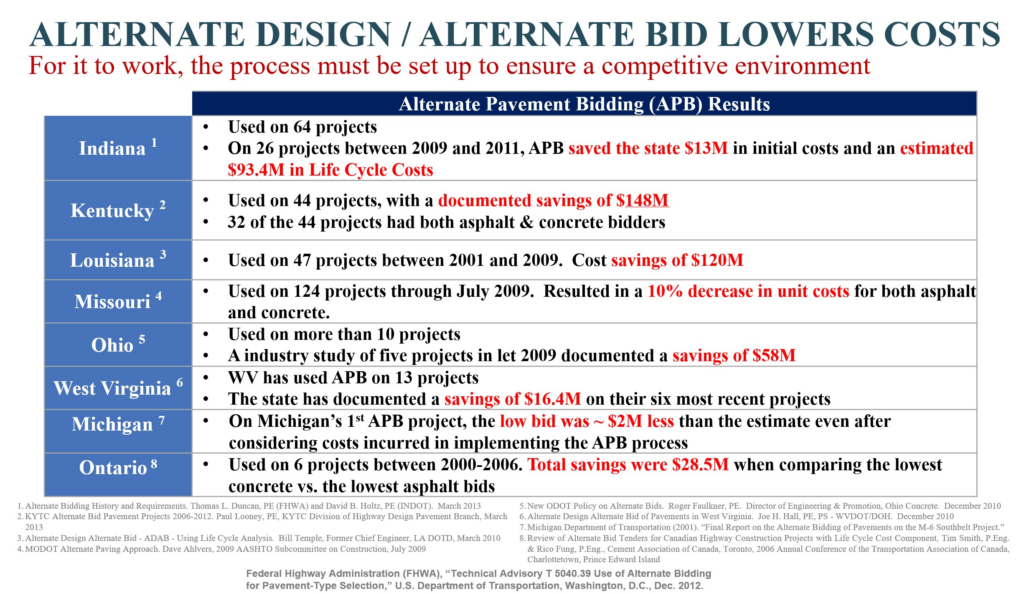

Once both industries are up and running, use Life Cycle Cost Analysis and Alternate Pavement Bidding on Specific Pavement Projects

LCCA and ADAB can only be used to obtain competition-based savings once an agency has instilled regular, long term competition into their pavement type selection process and it has become standard practice.

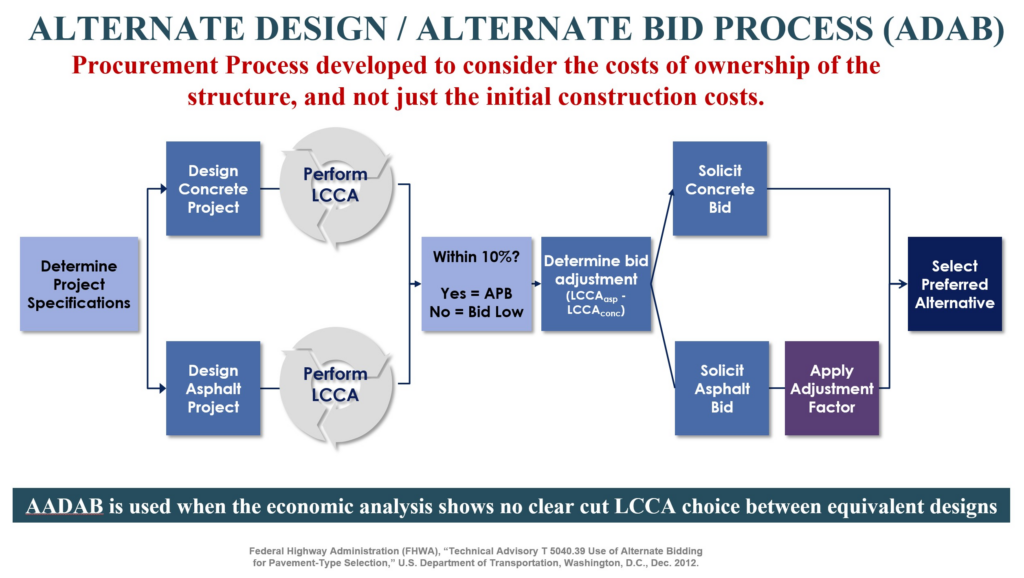

- Life Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA) quantifies the total “costs of ownership” over the pavement life. It is standard economic procedure used to compare competing alternative designs, over a defined analysis period, considering initial cost as well all future maintenance and rehabilitation costs, expressed in equivalent present value dollars.

- Alternate Design / Alternate Bid (ADAB) is a bidding process where two equivalent pavement designs are developed for a given project and the contractor then chooses on which pavement type to submit for his bid. The owner then evaluates the proposals using LCCA and the alternative with lowest total “costs of ownership” wins. Because more paving contractors from both industries can compete, it drives down costs.

To instill Life Cycle Cost Analysis and an Alternate Design / Alternate Bid program, DOTs should follow the process outlined by USDOT Federal Highway Administration in their Guidance on LCCA and ADAB.

summarized

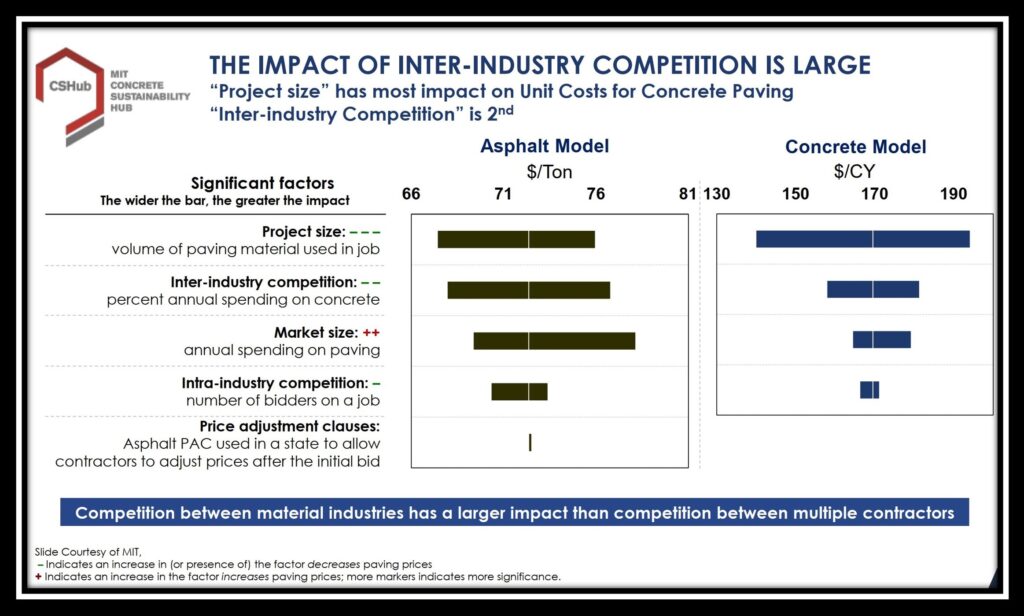

State Departments of Transportation have the unique opportunity to influence market dynamics and pricing of pavement materials. Because ALDOT is the primary purchaser of a major “commodity” (pavement), they can leverage their purchasing power to create inter-industry competition that results in long term bid-price changes.

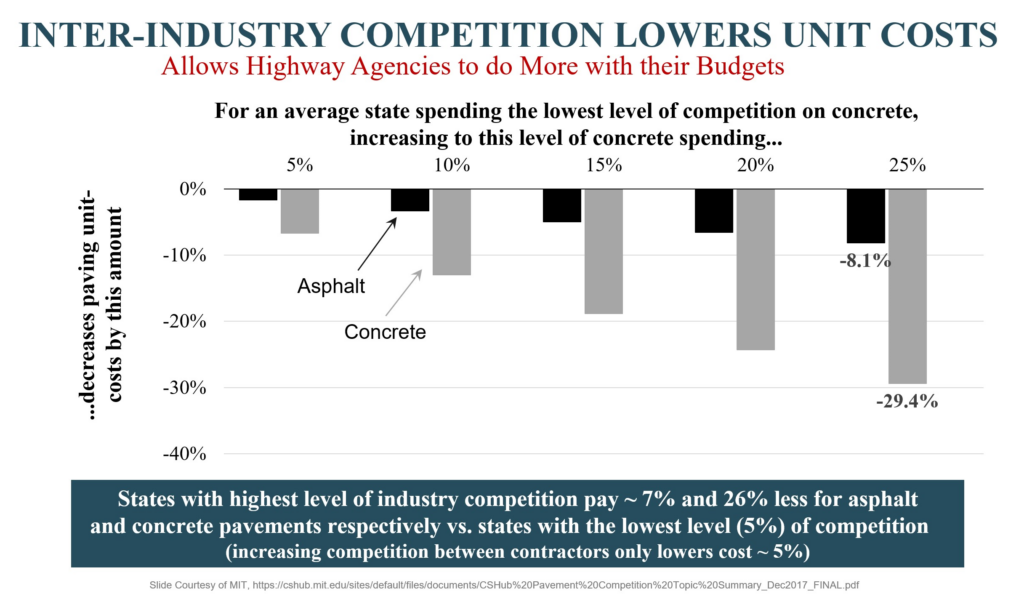

As a comparison, increasing Intra-Industry (same material) Competition from the lowest 25% of competition to the highest 25% of competition only reduces costs for an “average” project by 5%.

Policies that lead to a more balanced paving market share are more effective in reducing unit costs than simply increasing the number of bidders in the bidding process. States that have the highest 25% of competition (i.e. high concrete pavement market share) should expect to pay at least 7% and 26% less than states in the lowest 25% of competition for a typical asphalt and concrete project, respectively.

Agencies should therefore proactively pursue policies that increase market diversity because when states purposely invest in both concrete and asphalt paving over an extended time period, they pay significantly less for both paving materials.